Heart failure occurs when cardiac output is insufficient to meet the physiological requirements of the body.

Introduction to Heart Failure

There are two main things to consider with heart failure:

- Is the heart failure right sided or left sided?

- Is it a systolic failure or a diastolic failure?

When the heart beats, it ejects a volume of blood known as the stroke volume. Not all of the blood that is in the heart gets ejected into the body with each beat – some of it remains in the heart. The volume of blood in the heart at the end of diastole i.e. just before the heart contracts, is known as the end diastolic volume.

If you divide the stroke volume by the end diastolic volume, you get the ejection fraction i.e. the fractional volume of blood which is ejected from the heart. A normal ejection fraction is usually between 55%-75%.

Important Definitions

- Preload: How stretched the cardiac myocytes are at the end of diastole i.e. just before systole.

- Afterload: The force of resistance that the heart has to contract against to eject blood during systole.

- Frank-Starling principle: As pre-load increases, contractility increases which results in a larger stroke volume. However, this plateaus after a certain pre-load and eventually begins to drop.

Systolic Heart Failure

- Systolic heart failure is where the heart is unable to contract properly, meaning the stroke volume with each beat is reduced.

- So, stroke volume drops but a lot of blood is still hanging around in the heart itself, meaning end diastolic volume is high. This results in a reduced ejection fraction (lower numerator i.e. stroke volume but same denominator i.e. end diastolic volume).

Causes include:

- Ischaemic heart disease

- Previous myocardial infarction resulting in scar tissue, meaning there is less viable contractile tissue

- Dilated cardiomyopathy

Diastolic Heart Failure

- This is where the heart cannot relax properly, and therefore does not fill normally. Due to Starling’s law of the heart, the reduced filling of the heart > reduced heart stretch and thus lower end diastolic volume > lower stroke volume.

- However, since both end diastolic volume and stroke volume are dropping together, ejection fraction is maintained in heart failure.

Causes include:

- Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) due to long-standing hypertension.

- This type of hypertrophy is concentric i.e. the sarcomeres are generated in parallel, meaning the chamber space reduces resulting in less space for blood to fill.

- Constrictive pericarditis

- Cardiac tamponade

- Restrictive cardiomyopathy: Stiffer myocardium so harder to fill the heart.

Compensatory Mechanisms in Heart Failure

Due to the drop in cardiac output, the body attempts to meet the physiological demands of the body through compensatory mechanisms. One important thing to remember is a reduced cardiac output results in a reduced blood pressure. The body tries to fix this via the following mechanisms:

- Sympathetic nervous system activation:

- Vasoconstriction helps to raise peripheral vascular resistance and thus blood pressure.

- Tachycardia will help to maintain a cardiac output. Remember, cardiac output = stroke volume x heart rate. If your stroke volume drops, then you could try to increase heart rate to maintain the cardiac output.

- Activation of the renin angiotensin system: Reduced cardiac output to the kidneys activates the renin angiotensin system. This results in water and salt retention, thus increasing circulating volume and blood pressure.

Left Ventricular Heart Failure

Reduced cardiac output results in ‘backing-up’ of blood and pressures from the left ventricle, to the left atrium and into the pulmonary vein and pulmonary circulation, thus increasing hydrostatic pressures in the pulmonary circulation. When this pressure is greater than the oncotic pressure, fluid extravasates into the interstitial space and the alveoli, thus causing pulmonary oedema.

Clinical Features therefore include:

- Dyspnoea: Due to pulmonary oedema

- Orthopnoea/PND: When lying down, fluid in the peripheries redistributes to the lungs – as the lungs are already congested, this results in breathlessness.

- Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea (PND): Sudden attack of dyspnoea at night which usually wakes the patient up when asleep

- Orthopnoea: Breathlessness when lying down

- Cough which may be accompanied by a frothy pink sputum

- Cardiac asthma: Wheeze, cough, dyspnoea and bloody sputum

- Nocturia: Again, when lying down, blood redistributes the kidney from the peripheries. Restored blood flow to the kidneys can result in diuresis.

Causes of left sided heart failure include:

- Ischaemic heart disease: Ischaemia to the heart resulting in damage to the myocardium.

- Hypertension

- Dilated cardiomyopathy

- Aortic stenosis: The heart has to overcome a greater afterload to get blood through a narrowed aortic valve.

- Previous myocardial infarction

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health; originally uploaded by Wouterstomp at en.wikipedia., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Cardiac Failure Signs and Symptoms

Right Ventricular Failure

Reduced cardiac output results in ‘backing-up’ of blood and pressures from the right ventricle, to the right atrium and into the systemic circulation, thus raising systemic hydrostatic pressures. This causes oedema e.g. in the ankles, sacrum, peritoneal cavity (ascites) etc.

Clinical Features therefore include:

- Peripheral oedema: Fluid accumulating in the peripheries

- Ascites: Excess fluid accumulating in the peritoneal space

- Hepatosplenomegaly: Blood backing up into the liver and spleen

- Facial engorgement

- Epistaxis

- Raised jugular venous pressure

Causes of right sided heart failure include:

- Secondary to left sided heart failure as the congested pulmonary system results in a higher afterload for the right ventricle which eventually begins to fail.

- Chronic lung disease – see article on cor pulmonale

- Left to right cardiac shunt e.g. an atrial or ventricular septal defect resulting in blood flowing from the high pressure left circulation in the right side of the heart.

New York Heart Association Classification of Heart Failure

This can be used to grade the severity of dyspnoea associated with heart failure.

- I: Ordinary activities do not cause fatigue/palpitations/dyspnoea

- II: Comfortable at rest but ordinary physical activity causes fatigue/palpitations/dyspnoea

- III: Comfortable at rest but less than ordinary activity causes fatigue/palpitations/dyspnoea

- IV: Unable to carry out activity without difficulty, and symptoms are present at rest.

Investigations

Bedside

- History & examination. Specific signs of heart failure include:

- Raised JVP

- Hepatomegaly

- Oedema

- Respiratory signs such as basal crackles

- Gallop rhythm on auscultation of the heart (S3 and S4)

- Displaced apex beat

- ECG: May show signs of left ventricular hypertrophy which can be seen by large amplitude QRS complexes.

Bloods

- FBC, U&E, LFT, lipid panel, thyroid function test, HbA1c

- N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP): This is a major diagnostic tool used in the NICE guidelines as it informs referral and diagnosis.

- B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) is a hormone released by ventricles in response to stretch. It causes diuresis, vasodilation and natriuresis. NT-proBNP is simply an inactive fragment of this peptide.

- <400ng/L makes heart failure unlikely

- 400-2000ng/L should prompt urgent referral within a 6-week period to a specialist

- >2000ng/L should prompt urgent referral within a 2-week period to a specialist

Imaging

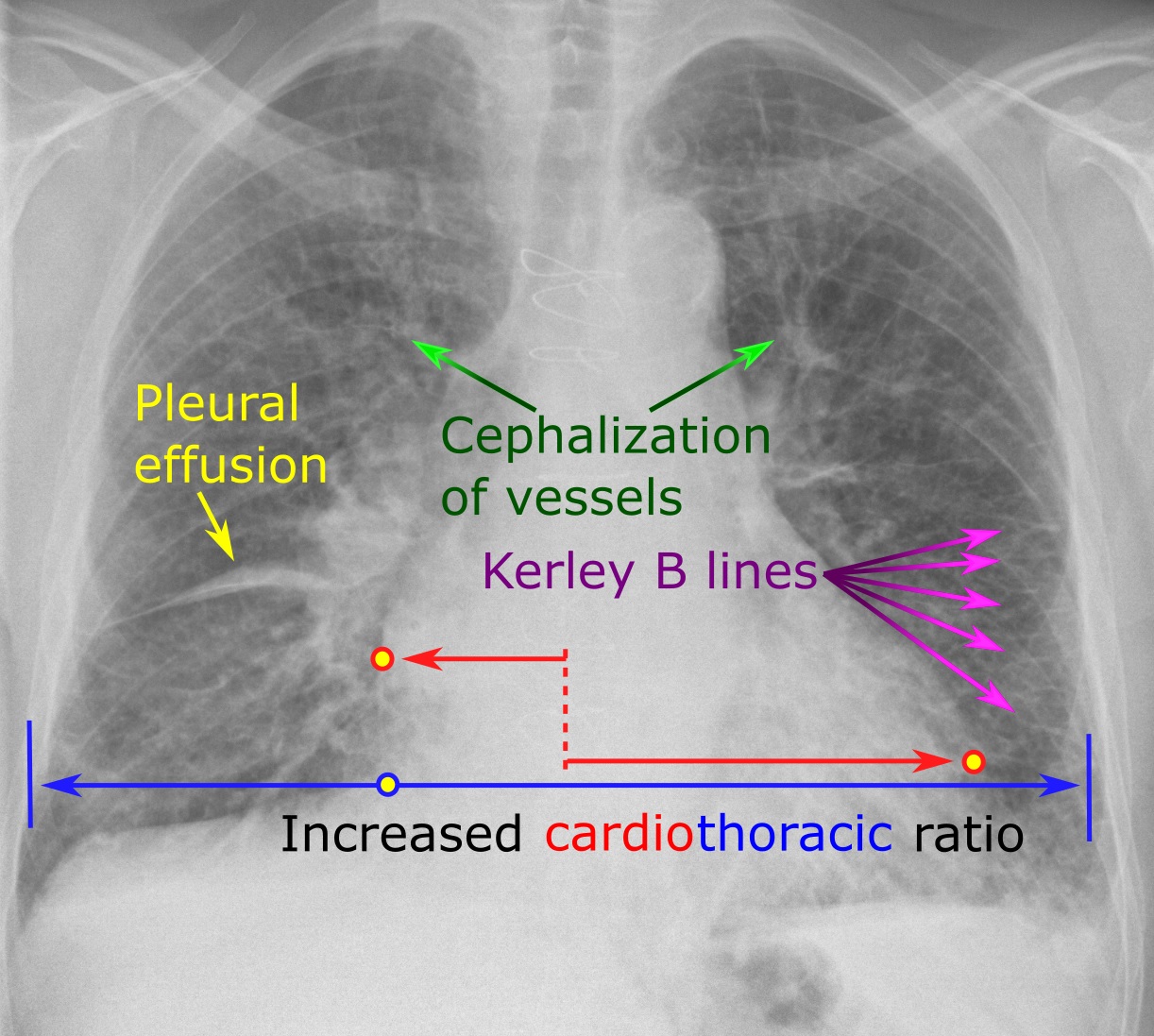

- Chest X-ray: You can remember the features of heart failure using ABCDE

- Transthoracic echocardiogram: This allows assessment of the ejection fraction, systolic and diastolic function and identification of valvular pathologies or cardiac shunts.

Differential Diagnosis

- Dyspnoea: Asthma, pulmonary embolism, lung cancer

- Peripheral oedema: Nephrotic syndrome, dihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers, hypoalbuminaemia

Management

Lifestyle advice is important, so patients should be given advice regarding smoking cessation and alcohol intake. NICE guidelines on the pharmacological therapy for patients with heart failure with a reduced ejection fraction includes the following:

- ACE inhibitor + beta-blocker for first-line therapy.

- If the patient is not tolerating ACEi, an angiotensin II receptor blocker can be prescribed instead. Each of these should be started one at a time.

- Three beta-blockers are licensed in the UK for treating heart failure: Nebivolol, carvedilol and bisoprolol.

- If patients continue to experience symptoms on the ACEi + Beta blocker, a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (spironolactone) can be added.

- Specialist drug treatments: These are used in specialist treatment for chronic heart failure.

- Ivabradine

- Hydralazine with nitrate e.g. isosorbide dinitrate: This is a vasodilator which can reduce mortality

- Digoxin: Used when heart failure hasn’t improved despite first-line therapy

- Sacubitril valsartan

- Diuretics: These are used to help with congestive symptoms. Loop diuretics are typically used.

Additionally, NICE guidelines state that heart failure patients be offered an annual influenza vaccination and a one-off pneumococcal vaccination. Screening for depression is also important in patients with chronic conditions.

References

https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/heart-failure/what-is-heart-failure/classes-of-heart-failure

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/16950-ejection-fraction

https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/cardiovascular-disorders/heart-failure/heart-failure-hf#v46183496

http://www.pathophys.org/heartfailure/#Pathogenesis

https://www.health.harvard.edu/newsletter_article/bnp-an-important-new-cardiac-test

https://www.sign.ac.uk/assets/sign147.pdf

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng106/chapter/recommendations#treating-heart-failure-with-reduced-ejection-fraction

https://cks.nice.org.uk/heart-failure-chronic#!prescribingInfoSub:18