Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD), is a condition where gastric fluid and acid refluxes into the oesophagus and mouth.

Pathophysiology

- The lower oesophageal sphincter is a ring of muscle found at the bottom of the oesophagus near the gastro-oesophageal junction. It is responsible for preventing reflux of stomach contents into the oesophagus. The sphincter is known to physiologically open and close on a transient basis to allow gas to escape from the stomach. These are known as transient relaxations of the lower oesophageal sphincter.

- Should these increase in number, they can allow stomach contents to be refluxed. Anything affecting the function of the lower oesophageal sphincter can cause reflux. For example, lying down after a heavy meal can place pressure on the lower oesophageal sphincter, thus causing reflux of stomach acid.

- From stomach physiology, we are aware the stomach has highly specialised mechanisms that protects the mucosa from the harsh acidic environment. However, these protective physiological mechanisms are not present in the oesophagus, thus leading to damage to the oesophageal mucosa.

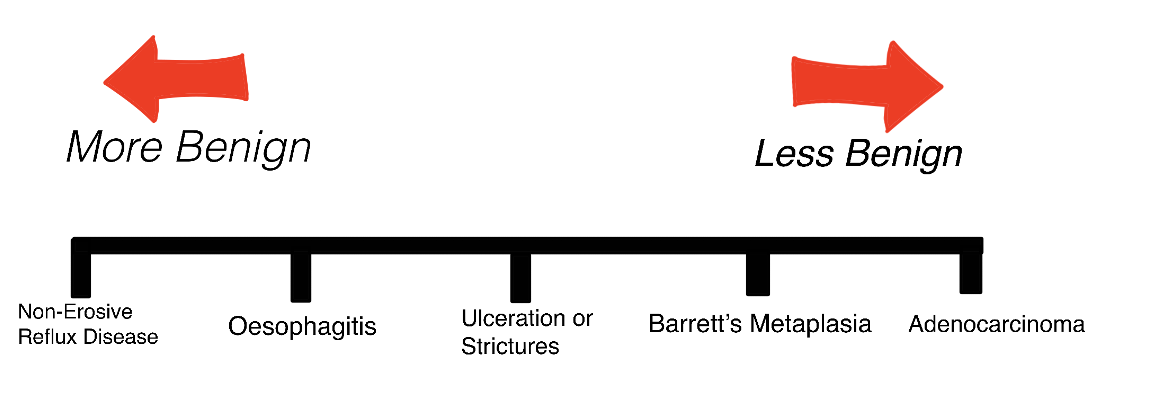

- A spectrum of disease exists in GORD, whereby some patients have non-erosive reflux disease i.e. they are symptomatic, but an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy would be negative. Some patients may develop oesophagitis which would be seen on endoscopy as a clearly inflamed and irritated oesophageal mucosa. This may progress into ulceration of the mucosa, oesophageal strictures or Barrett’s metaplasia.

Copyright Medic in a Minute 2022

Schematic Showing Different Oesophageal Diseases

Risk Factors

- Obesity: Due to increased intra-abdominal pressure

- Hiatus Hernia: Disrupts pressure of the lower oesophageal sphincter

- Pregnancy: Due to increased intra-abdominal pressure

- Smoking

- Alcohol

- Drugs e.g. calcium channel blockers/nitrates by relaxing the lower oesophageal sphincter

Clinical Features

The features of dyspepsia are present in GORD. Dyspepsia is used to describe a group of symptoms including upper abdominal pain, reflux, nausea, and vomiting.

- Retrosternal pain (heartburn): caused by acid refluxing and irritating the oesophageal mucosa. Typically a burning pain which can be triggered/worsened by lying down after meals

- Upper abdominal pain: Usually epigastric

- Water brash: Phenomenon of increased salivation in the mouth.

- Belching

- Odynophagia (painful swallowing) due to oesophagitis

- Dysphagia (difficulty swallowing). The presence of dysphagia should prompt endoscopy.

- Nausea/vomiting

- Hoarse voice

- Foul breath

- Nocturnal cough

Differential Diagnosis

- Pancreatitis

- Gastritis

- Pneumonia

- Peptic ulcer disease

- Oesophageal spasm

- Myocardial infarction

- Musculoskeletal pain

Red Flag Symptoms

The following symptoms should prompt oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (OGD). Endoscopy may reveal oesophagitis or Barrett’s oesophagus.

- Dysphagia

- Weight loss

- Malaena

- Haematemesis

- Iron deficiency anaemia

- Progressive symptoms

- Treatment resistant dyspepsia

- High platelet count

Investigations

Bedside

- History and Examination

- ECG: Rule out cardiac pathology

Bloods

- FBC: Rule out iron deficiency anaemia

- U&E, LFT, TFT: Baseline

Special Tests

- Endoscopy: All patients with dysphagia should be offered a 2-week referral for OGD. Anyone aged 55+ with weight loss and either upper abdominal pain, dyspepsia or reflux should also be offered a 2-week referral.[i]

- Oesophageal pH Monitoring: A pH sensor is placed into the oesophagus and pH is subsequently monitored, usually for 24 hours. If the pH in the oesophagus is less than 4, it confirms a reflux episode.[ii] This can be performed in cases where an upper GI endoscopy is negative.

GORD Management

Conservative

Lifestyle changes can be made such as weight loss, avoiding late night meals (particularly heavy meals), smaller meals, raising the head of the bed, reducing tea/coffee/alcohol consumption, and smoking cessation.

Antacids or alginates can help to relieve symptoms. Antacids are drugs which neutralise stomach acid e.g. calcium salts such as calcium carbonate.[iii] Alginates on the other hand create a foamy ‘raft’ barrier which sits on top of the stomach acid, preventing it from refluxing into the oesophagus.[iv]

Medical

The following is based on the NICE guidelines for GORD and dyspepsia management.

- Patients with GORD should be given 4-8 weeks course of a full-dose proton pump inhibitors (PPI). Examples of PPIs include:

- Lansoprazole

- Omeprazole

- Pantoprazole

- Esomeprazole

- If symptoms persist after this time, a PPI should be continued but at the lowest dose needed to manage symptoms.

- If there is inadequate response to a PPI, a H2 receptor antagonist can be offered instead. Examples include:

High Dose vs Full Dose of a PPI

The difference between high dose, full dose and low dose PPIs:[v]

| PPI | High (Double) Dose | Full (Standard) Dose | Low Dose |

| Omeprazole | 40mg OD | 20mg OD | 10mg OD |

| Lansoprazole | 30mg BD | 30mg OD | 15mg OD |

Surgical

For patients who cannot, or do not want to, continue to take acid suppression drugs, surgical treatment options are available. A laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication involves wrapping the fundus of the stomach around the lower oesophageal sphincter to strengthen the sphincter.

Oesophagitis Management

Patients with oesophagitis should be treated with 8-weeks of a full dose PPI. If this is insufficient, a high dose PPI or alternative PPI can be offered.

Complications

Barrett’s oesophagus is a pre-malignant complication of GORD. Prolonged exposure to stomach acid leads to mucosal irritation and erosion which leads to a transformation of the epithelium from normal stratified squamous epithelium to a metaplastic columnar epithelium (the latter of which closely resembles the epithelium of the stomach). Barrett’s oesophagus can subsequently develop into adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus.

It is important to note that not all patients with GORD will develop Barrett’s oesophagus and likewise, not all patients with Barrett’s oesophagus will develop oesophageal adenocarcinoma.

References

[i] NICE. Suspected cancer: recognition and referral. [internet]. 2017. [cited 20th July 2019]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng12/chapter/1-Recommendations-organised-by-site-of-cancer#upper-gastrointestinal-tract-cancers

[ii] Kumar and Clark’s

[iii] Singh P and Terrell JM. Antacids. [internet]. 2019. [cited 20th July 2019]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526049/#_article-17636_s2_

[iv] Leiman DA, Riff BP, Morgan S, Metz DC, Falk GW, French B, Umscheid CA and JD Lewis. Alginate therapy is effective treatment for GERD symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. [internet]. 2017. [cited 20th July 2019]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6036656/

[v] NICE. Appendix A: Dosage information on proton pump inhibitors. [internet]. 2014. [cited 20th July 2019]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg184/chapter/Appendix-A-Dosage-information-on-proton-pump-inhibitors