Asthma is a chronic, atopic condition, where patients experience airway hyperresponsiveness in response to ordinary stimuli. This article discusses asthma in adults.

Pathophysiology

Atopy is a genetic tendency to produce IgE in response to the exposure of common antigens.

Asthma is an atopic condition and is one of three other conditions which constitute the atopic triad, with the other two being allergic rhinitis (hay fever) and atopic dermatitis (eczema).

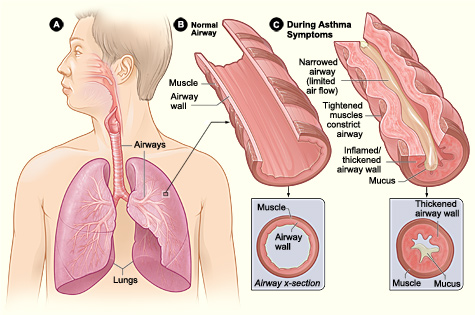

Whilst the precise pathophysiology of asthma is incompletely understood, we do know that individuals with asthma suffer from airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR), which basically means the airways get way more narrow in response to a particular stimulus vs someone healthy, in which that stimulus would cause little to no response in the airways. The basic pathophysiology of asthma is as follows:

- People with asthma overexpress Th2 cells.

- Exposure to a trigger/antigen causes production of inflammatory cytokines by Th2 cells, as well as IgE production.

- IgE antibodies bind to mast cells, causing release of inflammatory mediators such as histamine, leukotrienes and prostaglandins which leads to bronchospasm, inflammation and excessive production of mucus.

- The bronchospasm, inflammation (which will result in mucosal oedema) and increased mucus production cause airway obstruction, which is what leads to the symptoms you see in asthma.

United States-National Institute of Health: National Heart, Lung, Blood Institute, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Asthma

Asthma is therefore a type I hypersensitivity reaction as it is mediated by IgE.

Triggers

Asthma is caused by a combination of environmental and genetic factors. However, the trigger for symptoms typically comes from environmental antigens. They include:

Indoor Triggers

- House dust mites

- Cockroach residues

- Allergens from pets e.g. cats, dogs, budgies

Outdoor Triggers

- Cold Air

- Exercise

- Cigarette smoke

- Environmental allergens e.g. fungal spores or pollen

- Occupational triggers e.g. epoxy resin, isocyonates, flour dust and latex proteins

Clinical Features

Asthmatics usually have intermittent signs and symptoms. These include:

- Dyspnoea

- Coughing

- Chest tightness

- Wheezing: Typically, an expiratory polyphonic wheeze.

- Think of all the different airways in the lungs which contain a varying amount of mucus obstructing each airway.

- When air moves through these airways, it will produce a polyphonic (variable pitch) wheeze due to air moving through varying degrees of obstruction.

- Diurnal variation: Worse in late evening and early morning

Investigations

The following investigations and threshold values provided are based off of the UK NICE guidelines for asthma diagnosis in adults.

Bedside

- Peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR): Can measure PEFR for 2-4 weeks if there is diagnostic uncertainty following FeNO and spirometry. A variability of at least 20% between the highest and lowest reading is positive.

- Social history: Check for occupational asthma (are symptoms better on holidays/do colleagues have similar symptoms?)

Bloods

- FBC: May show eosinophilia

Imaging

- Chest X-Ray: Rule out other differentials

Special Tests

- Fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO): >40 parts per billion is positive.

- Spirometry: FEV1/FVC < 0.7 is an obstructive pattern, in keeping with an asthma diagnosis.

- A bronchodilator can be administered if an obstructive pattern is present to look for an improvement in FEV1. An improvement of at least 12% is positive.

- Direct bronchial challenge: If there is still diagnostic uncertainty following PEFR monitoring, direct bronchial challenge with histamine or methacholine is offered – these will cause a fall in FEV1 in someone with asthma.

Differential Diagnosis

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Absence of reversibility and usually have a positive history of smoking although a smoking history does not exclude asthma.

- Cystic fibrosis: Typically presents in younger age; can perform sweat chloride test to exclude

- Pneumothorax: Likely to have a more acute onset of symptoms

- Pulmonary embolism: Likely to have a more acute onset of symptoms

- Bronchiectasis

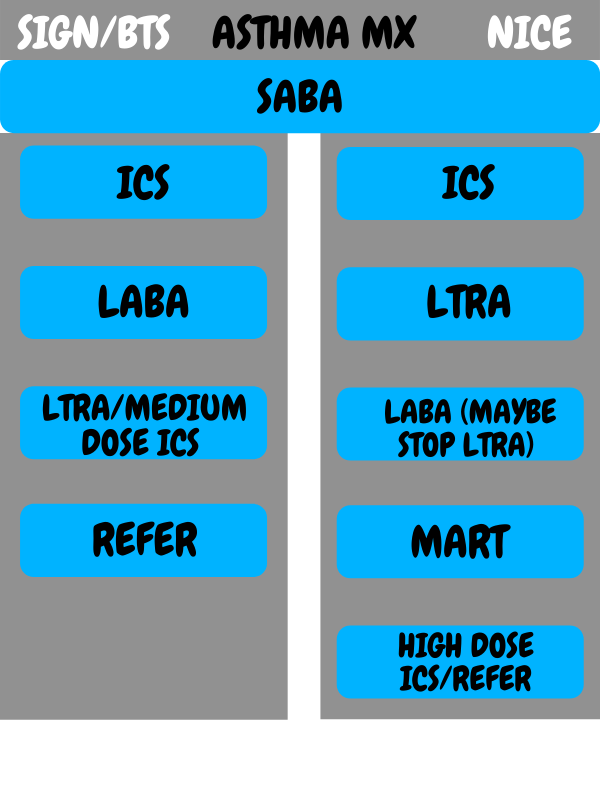

Management – BTS and SIGN

Several bodies have released guidelines on asthma management. The following information references the BTS and SIGN asthma guidelines (see below for NICE). Patients are started off on step 1 and moved up or down through the different treatment steps depending on how symptomatic they are despite treatment.

- Step 1: Short-acting beta-2 agonist (SABA). If patient has had an asthma attack in previous two years, symptomatic >3 times a week, waking one night a week or using SABA >3 times a week, step 2 is initiated.

- Step 2: Add low dose inhaled corticosteroid (ICS)

- Step 3: Add long-acting beta-2 agonist (LABA)

- Step 4: Either increase ICS to medium dose or add a leukotriene receptor antagonist (LTRA). Stop the LABA if no response.

- Step 5: Refer to specialist. Examples of specialist treatments include theophylline, anti-IgE monoclonal antibodies and oral steroids.

SABA: Salbutamol

ICS: Beclometasone dipropionate, fluticasone propionate, budesonide

LABA: Salmeterol

LTRA: Montelukast

The aim is to achieve asthma control which includes no night waking, asthma attacks, limitations of activity, daytime symptoms or rescue medication. Furthermore, aiming for PEF greater than 80% of predicted or best value.

Management – NICE

Although NICE guidelines do not delineate the treatment into distinct steps, we have done so for sake of simplicity.

- Step 1: SABA

- Step 2: Add low dose ICS if symptomatic >3 times a week or waking at night or uncontrolled asthma

- Step 3: Add LTRA

- Step 4: Add LABA and consider stopping the LTRA

- Step 5: Consider maintenance and reliever therapy (MART) regimen, consisting of a low dose ICS

- Step 6: Increase ICS to high dose/trial theophylline/trial long-acting muscarinic antagonist/specialist support

Copyright Medic in a Minute 2022

Quick Reference Guide for Asthma Management

Aspirin Exacerbated Respiratory Disease (Samter’s Triad)

- Some people have what’s known as aspirin-sensitive asthma.

- By ingesting salicylate or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) drugs such as aspirin, there is inhibition of the COX-1 enzyme.

- This leads to the production of cysteinyl leukotrienes which trigger asthma. Thus, aspirin-sensitive asthma is a non-IgE mediated form of asthma.

- Onset is typically in adults, between the ages of 20 and 50.

Samter’s triad includes 3 main features– asthma, aspirin/NSAID sensitivity and nasal symptoms. Nasal symptoms include rhinorrhoea, nasal polyps, rhinitis and anosmia.

References

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5951071/#__sec4title

http://www.allergy.org.nz/Allergy+help/samters+triad.html

https://www.aaaai.org/conditions-and-treatments/library/asthma-library/aspirin-exacerbated-respiratory-disease

https://brit-thoracic.org.uk/quality-improvement/guidelines/asthma/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6157154/#Sec4title

Davidson's Principles and Practice of Medicine, 23rd edition

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng80/chapter/recommendations#diagnostic-summary

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng80/chapter/Recommendations#pharmacological-treatment-pathway-for-adults-aged-17-and-over