A pulmonary embolism (PE) is when an artery in the lungs becomes blocked by an embolus.

Causes

- An embolus is an insoluble mass which travels from elsewhere in the bloodstream and is subsequently capable of blocking a blood vessel.

- The most common cause of a pulmonary embolism is a thromboembolus i.e. a blood clot from elsewhere in the body.

- Thromboemboli can come from various sources, including deep vein thromboses (DVTs) in the legs which become dislodged and travel to the lungs.

- Other causes of PEs include:

- Thromboemboli: From atrial fibrillation due to stagnant blood

- Septic emboli e.g. from infective endocarditis

- Fat emboli e.g. following a bone fracture

- Air emboli e.g. iatrogenic embolus from administration of IV fluids

- Amniotic fluid emboli

You may hear the term venous thromboembolism (VTE) used frequently. This refers to both pulmonary emboli and DVTs.

Pathophysiology

Virchow’s triad is a triad comprising of 3 factors which contribute to thrombosis. Changes in any of the following increase the risk of a PE:

- Blood flow: Stasis or turbulent blood flow can lead to thrombus formation.

- Hypercoagulability: Blood contains several factors that promote clotting. A change in the composition of blood can therefore promote thrombi formation.

- Vessel wall damage: The vascular endothelium protects blood from the thrombogenic sub-endothelium. Thus, damage to blood vessel walls and exposure of the sub-endothelium can promote thrombosis.

Risk Factors

- Recent immobilisation e.g. surgery/bed-rest (Blood flow)

- Lower limb trauma/fracture

- Varicose veins (Blood flow)

- Active cancer (Hypercoagulability)

- High oestrogen states such as pregnancy/combined contraception (Hypercoagulability)

- Thrombophilia (Hypercoagulability)

- History of deep vein thrombosis or PE

Clinical Features

As the lungs have a dual blood supply from the pulmonary and bronchial vasculature, collateral blood supply can allow smaller emboli to remain asymptomatic. However, when symptoms are present, patients may present with:

- Dyspnoea

- Acute pleuritic (worsens with breathing) chest pain, particularly unilateral

- Haemoptysis

- Hypoxia

- Tachypnoea

- Tachycardia

- Fatigue

- Low grade fever

- Pleural rub

- Raised JVP

- Unilateral warm, swollen, tender and red leg (sign of a DVT)

In more severe cases:

- Syncope

- Haemodynamic instability i.e. hypotension in the case of a very large clot which is obstructing blood follow through the lungs and back into the left side of the heart

- Sudden death due to obstruction of blood supply to the lungs. This can particularly happen in case of a large ‘saddle embolus’ – this is an embolus which sits in the pulmonary saddle, thus blocking a significant proportion of pulmonary blood flow, meaning the heart will struggle to pump oxygenated blood to the body.

Differential Diagnosis

- Pneumonia

- Pneumothorax

- Myocardial infarction

- Aortic dissection

- GORD

- Musculoskeletal pain

Investigations

Bedside

- Observations: Tachycardia, tachypnoea

- ECG:

- The most common finding is sinus tachycardia.

- Some patients may have the S1Q3T3 pattern (large S wave in lead I, Q wave in lead III and inverted T waves in lead III).

- Signs of right heart strain e.g. right axis deviation due to a dilated right atrium, RBBB, p pulmonale due to right atrial enlargement (large, tall p waves)

- Also helps to rule out alternative causes of chest pain e.g. MI

Bloods

- FBC: Baseline + platelets will be important if the patient will be prescribed low-molecular weight heparin and low platelets can be a contraindication for this.

- U&E: Baseline for long-term anticoagulation therapy + CTPA (contrast-based scan so need to know the renal function)

- Clotting Screen: Prior to starting anticoagulation therapy

- LFT, TFT, CRP: Baseline

- Troponin: If suspecting a cardiac cause of chest pain

- D-dimer:

- Breakdown product of clots.

- It can be raised in many different conditions and states e.g. infection, trauma, smoking and more.

- It’s a test with high sensitivity, but low specificity with one paper showing 99.5% and 41% sensitivity and specificity respectively. (i.e. if it’s negative, you can be assured a PE is not present, but if it is positive, it does not necessarily mean there is a PE present).

- ABG: Looking for a respiratory failure/respiratory alkalosis due to hyperventilation from hypoxia

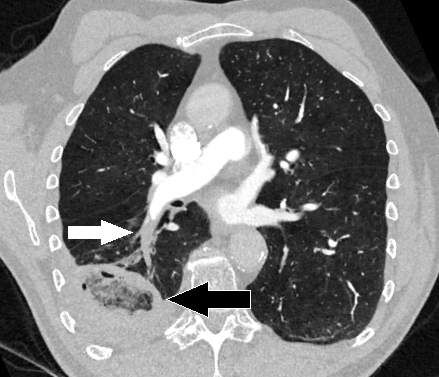

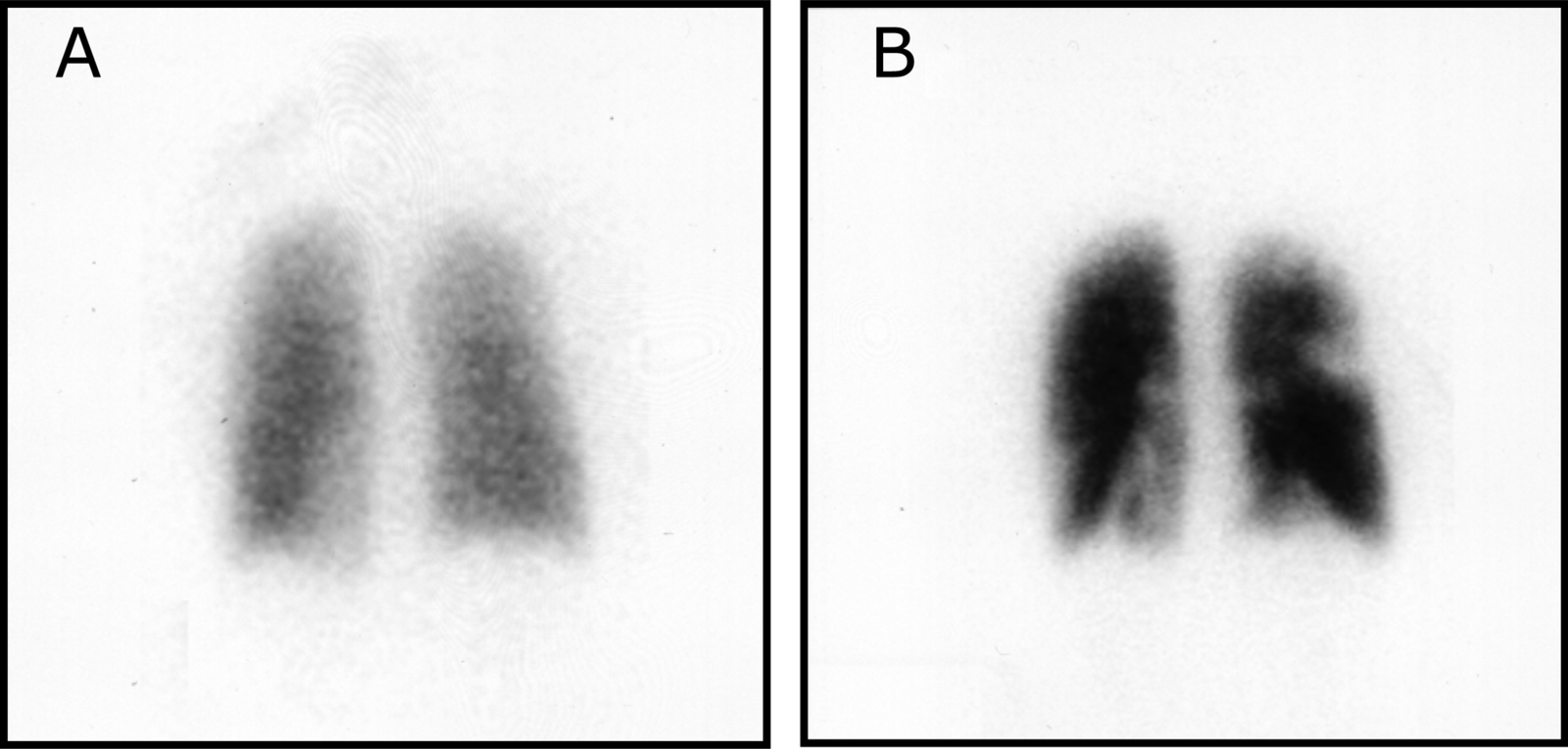

Imaging

Probability Scores

Most hospitals will have guidelines for the management of PEs, and they usually centre around a probability scoring system that guides further management. There are lots of different probability scores – two common ones used are the Wells’ score, and the PERC score.

Wells’ Score

| Feature | Description | Points |

| Clinical features of DVT | Leg swelling and pain when deep veins are palpated | 3 points |

| Alternative diagnosis is less likely than a PE | Alternatives include - GORD

- Pneumothorax

- Pneumonia

- Myocardial Infarction

- Heart Failure

| 3 points |

| Tachycardia | >100bpm | 1.5 points |

| History of DVT/PE | | 1.5 points |

| Surgery or immobilisation | - Surgery in last 4 weeks

- Immobilisation for at least 3 days

| |

| Haemoptysis | | 1 point |

| Cancer | - Palliative

- Currently being treated

- Received treatment in last 6 months

| 1 point |

Wells Score >4: PE is likely so

- CTPA (or V/Q if CTPA cannot be done)

- Interim anticoagulation is given when CTPAs cannot immediately be obtained

Wells Score <4: PE is unlikely – d-dimer needs to be done

- If d-dimer is positive: Arrange CTPA with interim anticoagulation if there will be a delay in getting a CTPA

- If d-dimer is negative: Consider alternative diagnosis

PERC Score

NICE recommend the use of the PERC score if the clinical suspicion of PE is low If any of the criteria are positive, a PE cannot be ruled out.

- Age ≥50

- HR ≥100

- O2 on room air <95

- Haemoptysis

- Unilateral leg swelling

- History of PE/DVT

- Recent surgery or trauma (within the last 4 weeks)

- Hormone use

Management

The mainstay of treatment for a PE is anticoagulation, which should be offered for a minimum of 3 months, or 3-6 months if someone has active cancer. This does not ‘shrink’ the clot itself – rather, it prevents formation of further clots. The body naturally breaks down the embolism over time.

There are three major types of anticoagulation used.

- DOACs: Direct oral anticoagulants. These are more commonly used these days as they don’t require monitoring.

- Apixaban and Rivaroxaban: These can be started immediately

- Edoxaban and Dabigatran: These require 5 days of pre-treatment with a short-acting anticoagulation i.e. low-molecular weight heparin (LMWH)

- Low-molecular weight heparin (LMWH): E.g. enoxaparin, dalteparin. These are usually started as initial treatment in inpatient settings as they act quickly, but patients will usually be switched to a DOAC eventually.

- Vitamin K antagonist: i.e. warfarin. Requires regular monitoring of the INR to ensure it is within range.

NICE Guidelines

- First-line: Direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) e.g. apixaban or rivaroxaban

- Renal impairment: Creatinine clearance (CrCl) = 15-50ml/min

- Apixaban or

- Rivaroxaban or

- LMWH for 5 days followed by edoxaban, or if CrCl dabigatran ≥ 30 ml/min or

- LMWH or unfractionated heparin (UFH) + vitamin K antagonist for at least 5 days or until INR is at least 2.0 on 2 consecutive readings, followed by vitamin K antagonist alone

- Renal impairment: CrCl < 15ml/min

- LMWH or

- Unfractionated heparin (UFH) or

- LMWH or UFH + vitamin K antagonist for at least 5 days/until INR is at least 2.0 on 2 consecutive readings, followed by vitamin K antagonist alone

- Active cancer

- Consider a DOAC; if a DOAC is not suitable then:

- LMWH or

- LMWH + vitamin K antagonist for at least 5 days/until INR is at least 2.0 on 2 consecutive readings, followed by vitamin K antagonist alone

- Antiphospholipid syndrome

- LMWH + vitamin K antagonist for at least 5 days/until INR is at least 2.0 on 2 consecutive readings, followed by vitamin K antagonist alone

- Haemodynamic instability

- Continuous unfractionated heparin infusion +/- thrombolysis

Inferior vena cava (IVC) filters are used where anticoagulation is contraindicated, or if anticoagulation treatment has failed.

Thrombolysis

In case of haemodynamic instability, thrombolysis is considered. Thrombolysis is enzyme-based breakdown of a clot (also used in treating ischaemic strokes) – it carries many risks including a risk of haemorrhage/bleeding so careful consideration needs to be made of risks vs benefits prior to administering it. Common agents include alteplase, streptokinase, and tenecteplase.

Unprovoked Pulmonary Embolism

Pulmonary emboli occurring without obvious precipitating factors require further investigation to rule out an undiagnosed cancer. Thus, according to NICE guidance, patients with unprovoked pulmonary embolisms should undergo routine bloods (FBC, U&E, LFT, Clotting) alongside a physical examination.

References

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6090438/#:~:text=Perrier%20et%20al%20(25)%2C,ranged%20between%2023%2D63%25.

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng158/resources/visual-summary-pdf-11193380893

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng158/chapter/recommendations#anticoagulation-treatment-for-pe-with-haemodynamic-instability